It turns out, along with many other parents under suspicion by Pittsburgh child welfare authorities, their crime is being poor. Though they are caring and vigilant parents to their own children, as well as generous volunteers helping other children in their community, this couple has been repeatedly flagged by social service databases for child neglect. In Pittsburgh, Eubanks meets Patrick and Angel. Many Hoosiers lost vital assistance because of such computer “mistakes.” This happened just as she was gaining weight, thanks to a lifesaving feeding tube, and learning to walk for the first time. At the age of 6, during Indiana’s experiment with welfare eligibility automation, Sophie received a letter (addressed directly to her) informing her that she was losing her Medicaid benefits because of a “failure to cooperate” in establishing her eligibility for the program.

The book is dedicated to a severely disabled little girl named Sophie. Indeed, as with the 19th-century poorhouse, she argues, the shiny new digital one allows us to “manage the individual poor in order to escape our shared responsibility for eradicating poverty.” Data can’t provide what poor people need, which is more resources. For the poor, she argues, government data and its abuses have imposed a new regime of surveillance, profiling, punishment, containment and exclusion, which she evocatively calls the “digital poorhouse.” While technology is often touted by researchers and policymakers as a way to deliver services to the poor more efficiently, Eubanks shows that more often, it worsens inequality. Virginia Eubanks begs to differ, with the authority to do so. We assume technology and the information it yields is making everyone’s life easier, freer and more comfortable. We’re seduced by similar smug, smart, supposed innovators hawking data’s potential to revolutionize health care and education. We tend to think that the smug, smart people who run companies like Google and Uber have some secret knowledge we even give them our personal information, uneasily, but ultimately with a bit of a shrug. Upper-middle-class professionals love data.

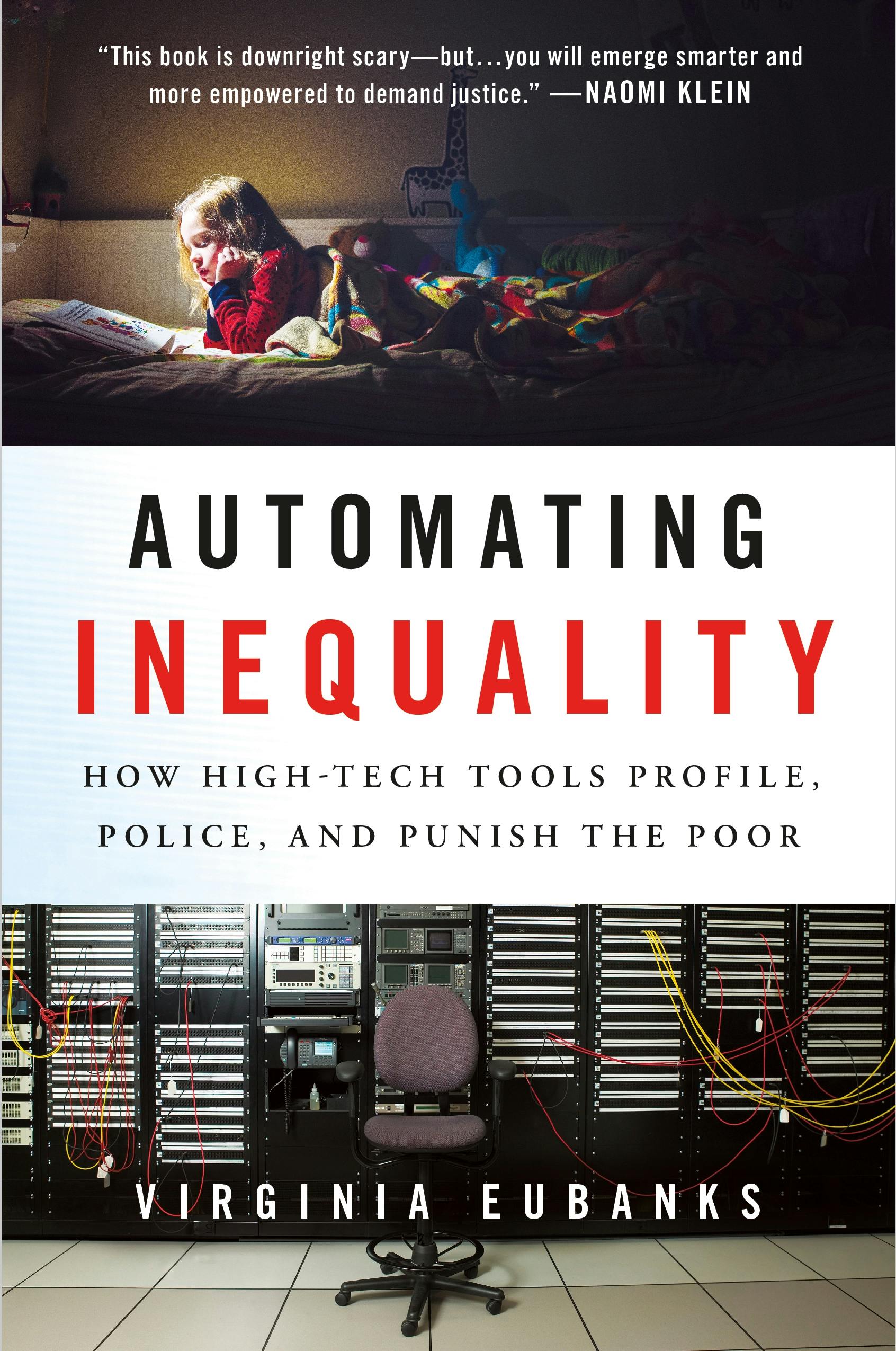

AUTOMATING INEQUALITY How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor By Virginia Eubanks 260 pp.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)